The Icelandic Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries has issued new five-year hunting permits for fin and minke whales, following advice from the Marine & Freshwater Research Institute. The permits allow for an annual catch of up to 161 fin whales and 217 minke whales through 2029, under strict quotas designed to ensure sustainable harvesting based on the precautionary approach to resource management.

The Icelandic Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries has issued new five-year hunting permits for fin and minke whales, following advice from the Marine & Freshwater Research Institute. The permits allow for an annual catch of up to 161 fin whales and 217 minke whales through 2029, under strict quotas designed to ensure sustainable harvesting based on the precautionary approach to resource management.

Despite being granted a license, Hvalur hf., the only company hunting fin whales in Iceland, has decided not to operate this summer. CEO Kristján Loftsson cited worsening market conditions in Japan — their primary export market — alongside the weak Icelandic króna, rising operational costs, and broader global economic instability.

"The price of our products is now so low that it is not justifiable to hunt this summer," Kristján Loftsson told Morgunblaðið. He added that the situation would be reassessed early next year.

Animal welfare concerns have also put increased pressure on Iceland’s whaling industry in recent years. In 2023, a government-commissioned report found that killing methods used in whaling often caused prolonged suffering for the animals. Following the report, the Minister of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries temporarily suspended whaling activities for several months and introduced stricter conditions for hunting permits, aiming to improve animal welfare standards going forward.

Currently, only fin whales and common minke whales may be caught in Icelandic waters, with all activities under careful government supervision. Other whale species remain fully protected.

A Long and Controversial History of Whaling in Iceland

Early Foreign Whalers

Early Foreign Whalers

Whaling around Iceland was historically carried out by foreigners. Basque whalers pioneered the industry in Europe during the 12th century, followed by the Dutch, Danes, and Norwegians. By the 16th and 17th centuries, Icelanders grew increasingly dissatisfied with the pollution and abandoned whale carcasses left in their fjords.

The First Ban

In 1915, Iceland banned whaling for at least ten years to protect fisheries, preserve the marine environment, and push back against foreign exploitation. The ban was lifted in 1928, and by 1935, new laws allowed only Icelandic ships to hunt whales within territorial waters.

The Modern Era Begins

Large-scale whaling returned with the founding of Hvalur hf. in 1948. For decades, Iceland actively pursued commercial whaling until international concerns over declining whale populations reshaped the global landscape.

Turbulence with the IWC

In the 1980s, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) called for a moratorium on commercial whaling. Iceland initially agreed but continued hunting under a scientific exemption until 1989. After tensions with the IWC, Iceland withdrew in 1992 and aligned more closely with the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). Despite attempts to find alternatives to the IWC, Iceland eventually rejoined in 2002 — but with a controversial reservation against the whaling ban.

Resuming Commercial Whaling

Iceland resumed scientific whaling in the early 2000s and reintroduced large-scale commercial hunting in 2006. Quotas expanded over the years, with 125 fin whales caught in 2009 and 148 in 2010 — the highest numbers in decades. However, following Japan's 2011 earthquake and tsunami, demand for whale meat collapsed, causing temporary pauses in Icelandic whaling.

Recent Years

After no fin whales were caught between 2019 and 2021, hunting resumed in 2022, when 148 fin whales were caught, followed by 24 in 2023. Now, in 2025, Hvalur hf. once again pauses its activities, citing the difficult economic climate. No fin whales were hunted in the year 2024.

Source: Visir, mbl, Ruv, Stjórnarráð Íslands

Related articles:

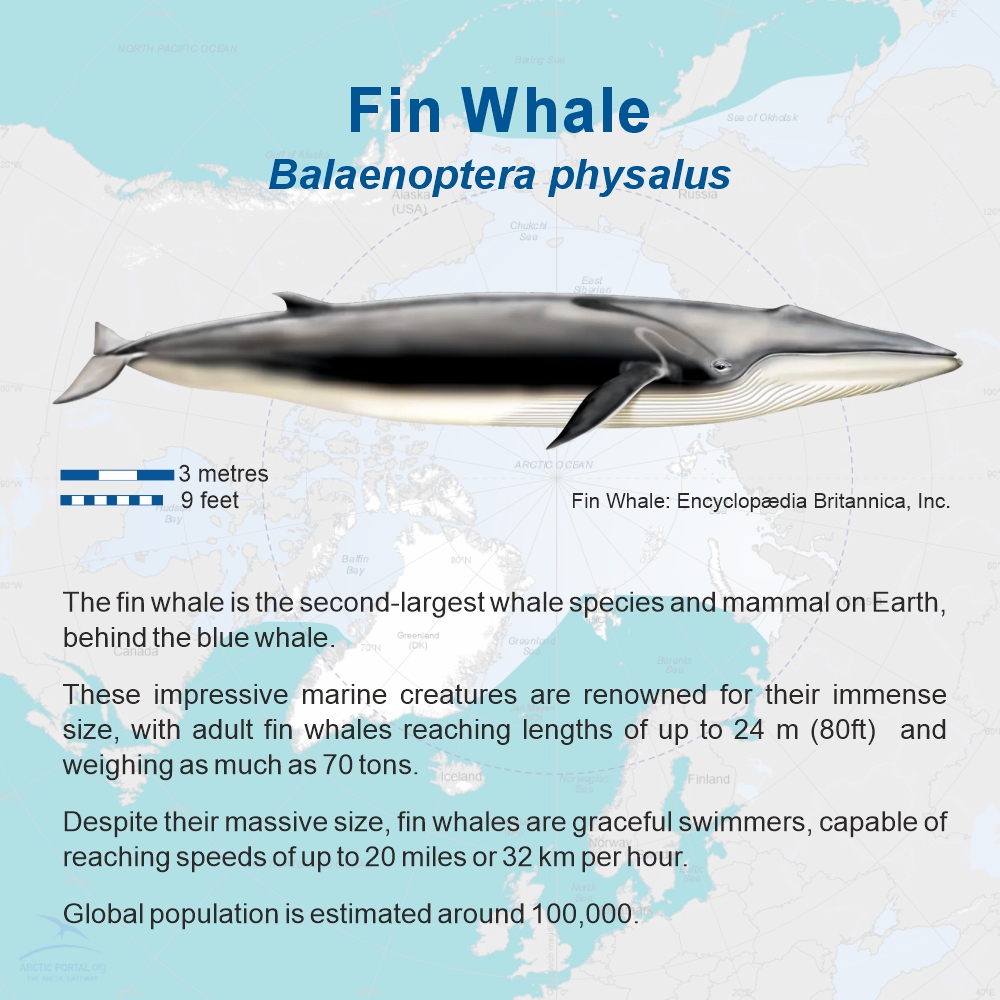

Quick-fact on the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

Quick-fact on the Bowhead Whale (Balaena Mysticetus)

Quick-fact on the Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus leucas)

Quick-fact on the Narwhal (Monodon monoceros)