An interesting article written by Andrey Krivorotov has now been published in the China in World and Regional Politics: History and Modernityyearbook by the Institute of Far Eastern Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow). In the article Dr. Krivorotov explores the U.S. - China relation in the North Atlantic, its potential developments and impact on Arctic countries with emphasis on Russia.

The article abstract

Since 2019, the U.S. Administration has included the Arctic into its overall China containment policy. Iceland and Greenland attract its special attention as traditional U.S. allies, which play key roles for the control over NATO’s vital maritime communications in North Atlantic, but which have lately developed vibrant contacts with PRC.

Greenland has been on the radar in Washington since World War II, regarded within the framework of the Monroe Doctrine, which, although voided officially, still influences the American foreign policy thinking. Now this approach is reinforced by the growing U.S. activities in the Arctic at large and by the global confrontation with Beijing. The key current interests of the United States in Greenland include the security of the strategically important Thule Air Base, preventing large Chinese investments, which would involve the island into the Polar Silk Road initiative, and a potential extraction of rare earth elements.

Since mid-2019, the U.S. have launched several major initiatives related to Greenland, the most famous one is President Trump’s offer to purchase it from Denmark. While China focuses on large scale mining projects which Greenland needs to obtain economic independence, and people-to-people contacts, the U.S. concentrate on public policy measures indicating a clear desire to put Greenland under a tighter American control bypassing Copenhagen. Denmark, although a close NATO ally of the United States, is concerned by the activities of both great powers and tries to become a good patron for Greenland to prevent its secession. Meanwhile, the Greenlandic authorities confirm their intentions to struggle for a full-fledged statehood, reflecting the moods of 2/3 of the population.

The article suggests three medium-term scenarios, with Greenland remaining in a gradually looser union with Denmark, moving into the U.S. domain or acquiring independence and thus becoming subject to a hard international competition. The next few years may be of special importance for further development, which will also affect Russia as the biggest Arctic nation.

Author: Andrey K. KRIVOROTOV, Ph.D. (Economics)

Author: Andrey K. KRIVOROTOV, Ph.D. (Economics)

Assistant Professor, Odintsovo branch of Moscow State Institute of International Relations (University) under the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Member of the International Arctic Social Science Association.

The full article

For nearly three decades after the Cold War, the Arctic was witnessing a remarkably low level of international tension, with a dramatically reduced military presence and an unparalleled cooperation on regional governance, environment, and indigenous peoples. It remained virtually unaffected even by the Russia-West standoff since 2014, giving rise to a popular concept of ‘Arctic exceptionalism’ [Käpylä and Mikkola].

However, around 2018 U.S. Navy officials started projecting the global tension to the North, and this became an official American policy during the Arctic Council Ministerial meeting in Rovaniemi in May 2019. Mike Pompeo, the U.S. Secretary of State, delivered a speech the day before the meeting, accusing Russia of aggressive behavior in the Arctic and voicing doubts about the Chinese intents. ‘The Pentagon warned just last week that China could use its civilian research presence in the Arctic to strengthen its military presence, including by deploying submarines to the region as a deterrent against nuclear attacks,’ Secretary said [Johnson and Wroughton]. The Ministerial itself became the first one not to adopt a joint statement, due to the U.S. disagreement with its climate goals. Soon after, in June 2019, the U.S. Department of Defense adopted its new Arctic Strategy with an outspoken focus on ‘limiting the ability of China and Russia to leverage the region as a corridor for competition’ [U.S. Department of Defense, 2019].

The passages on Russia look like reverting to a traditional Cold War rhetoric, reflecting the recent (rather limited, but highly publicized) partial restoration of the old Soviet military presence in the Arctic. Meanwhile, the focus on China is a brand new element, indicating that the Arctic is now involved in the global U.S. strategy of containing China.

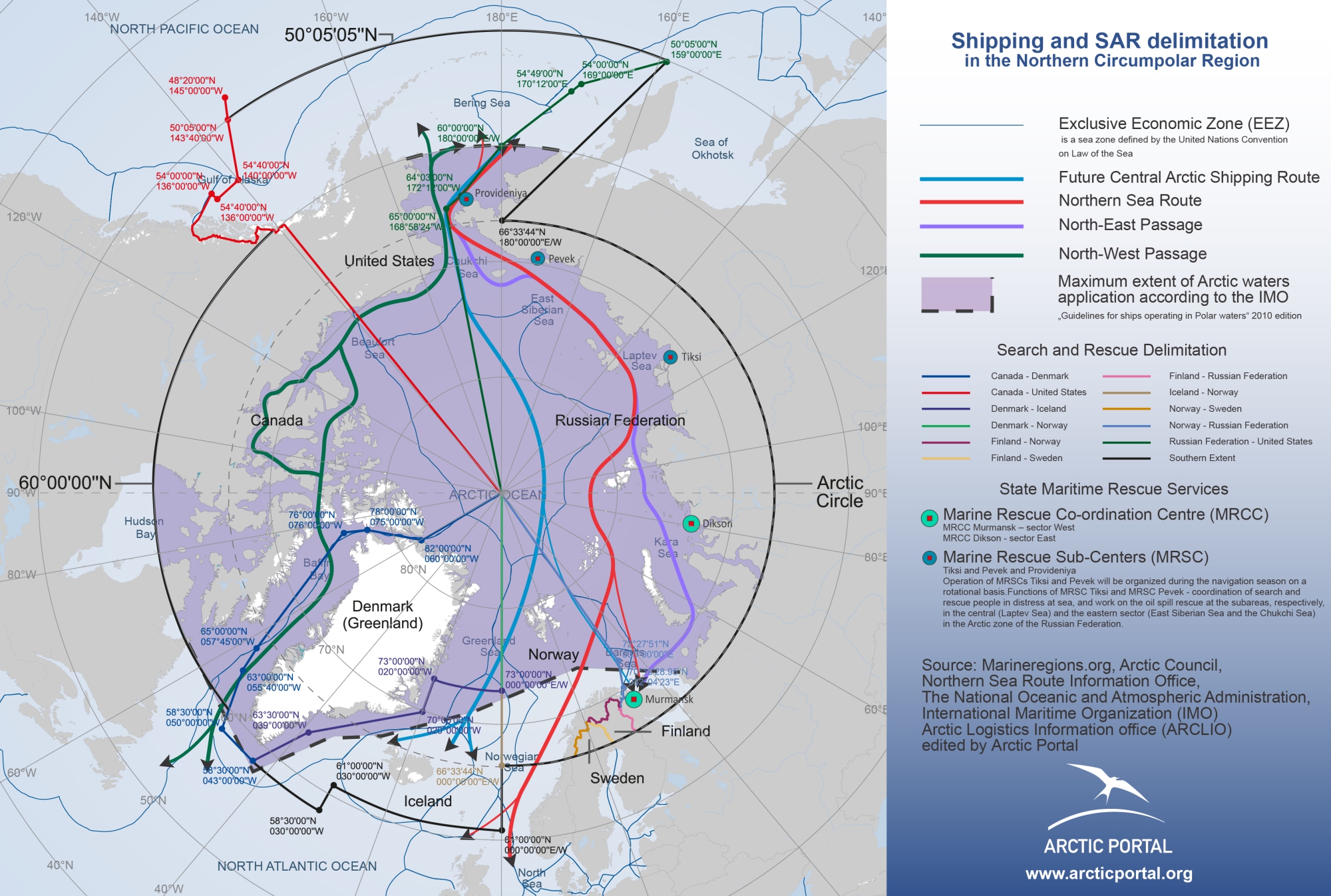

Iceland and Greenland, which both have close ties with China, attract special U.S. attention in the form of dramatically intensified official contacts and statements. In geostrategic terms, both islands belong to Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap (GIUK), crucial for the logistic ‘transatlantic link’ between the U.S. and its European allies. GIUK lost much of its importance for NATO after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but seems to have regained it now with the view to Russian and potentially Chinese naval presence [The GIUK Gap’s strategic significance].

This article focuses primarily on the development of Greenland as a new arena of China-U.S. competition.

Greenland-China relations and U.S. concerns

Greenland is the world’s biggest island with some 2.1 million sq. km of land area (mostly ice-covered) and merely 57,000 inhabitants. Together with the continental Denmark and the Faroe islands, it forms the Danish Kingdom, although in geographical terms, Greenland belongs to North America. Its capital, Nuuk, is some 4,000 km away from Copenhagen.

Denmark has an interest in the island as its only Arctic territory and an important asset in the bilateral relations with the U.S., but tends to give Greenland a growing autonomy [Kuo]. Under the Self-Government Act, which entered into force in 2009, Greenlandic authority covers nearly all issues but for foreign, security policy and currency emission. According to opinion polls, two thirds of the population favor secession from Denmark, but the Greenlandic economy is not self-sufficient, relying heavily on seafood (95% of exports) and the annual transfer from Copenhagen, the so called block grant. Developing its abundant natural resources, like metal ore and potentially hydrocarbons, is the island’s main hope for a rapid economic development and prosperity, and Chinese companies (often operating via, or in cooperation with, third countries) have been most active.

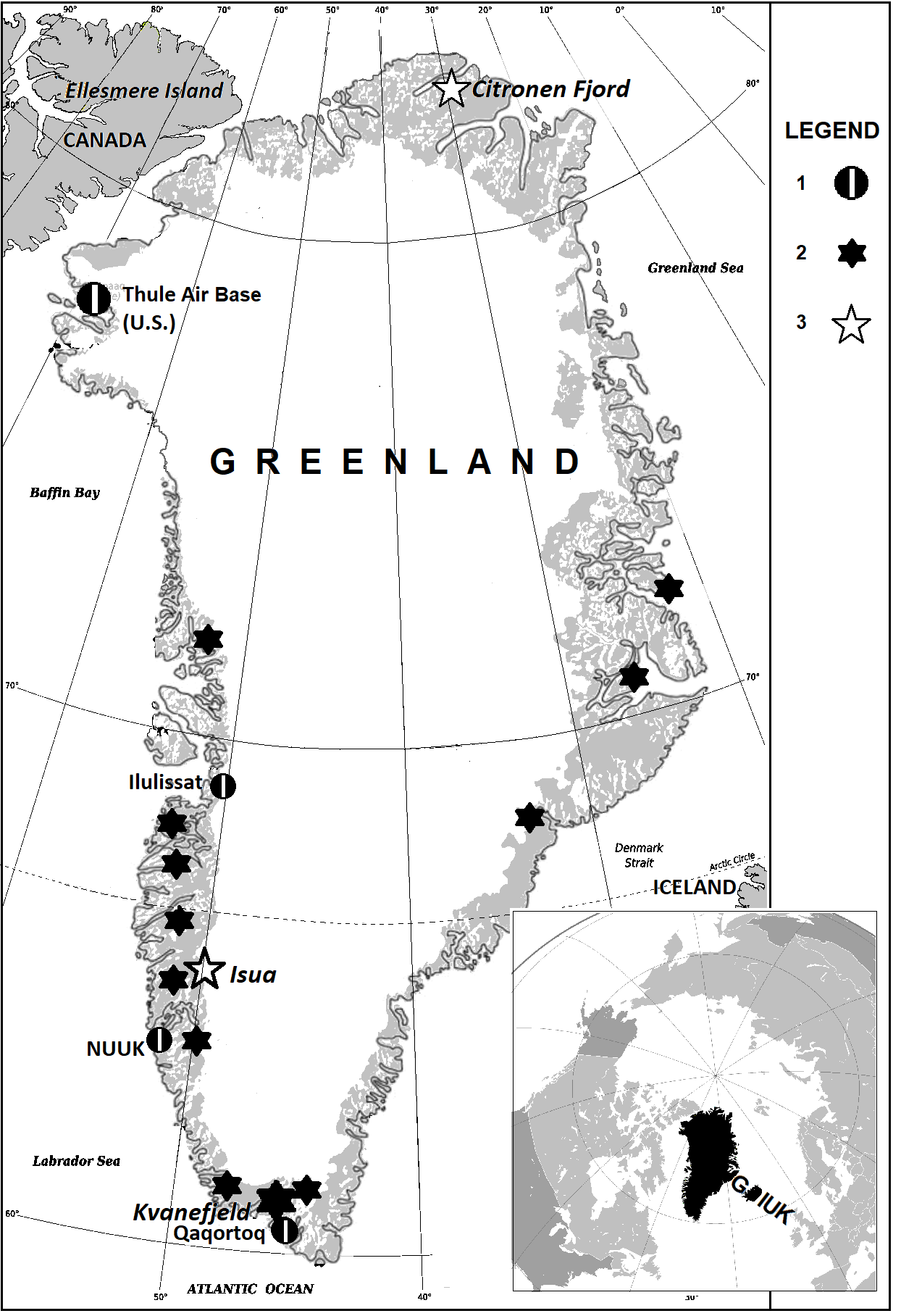

By late 2012, Chinese investors nearly made a massive entry into Greenland. Its government headed by Kuupik Kleist maintained a high-level dialog with Beijing and welcomed Chinese companies to several major projects. The most advanced was Isua iron ore mine 150 km north of Nuuk, to be constructed and operated by London Mining, a UK company with strong ties to Sichuan Xinye Mining Investment Co. But the subsequent government shifts in Greenland, bankruptcy of London Mining and the fall in raw material prices made the projects stall. The ruby mine of LNS Group from Norway is the only plant launched since then.

The mutual interest remained, however. Kim Kielsen, the present Greenlandic Prime Minister, paid a visit to China in 2017 to discuss opportunities for Chinese investments and hiring Chinese companies for the badly needed modernization and construction of three airports, in Nuuk, Ilulissat and Qaqortoq. It was presumably this latter issue that triggered the increased U.S. activity.

America has three key concerns about China-Greenland relations.

Military security is most widely articulated. In Thule in the north of the island, the U.S. operates an air force base, an anti-ballistic early warning radar and the only American deep water port in the Arctic. This presence is based on a special accord with Denmark of 1951, to which Greenland is also a signatory since 2004.

Military considerations obviously played a role in 2016 when Washington pressed on Copenhagen to halt the purchase of Grønnedal (Kangillinguit), a decommissioned U.S.-built naval base, by the Syangan-based General Nice Group, which now owns the Isua mine. Similarly, when the Greenlandic Government shortlisted China Communications Construction Company for the three airports contract in 2018, the Danish authorities got a strong public message from Katie Wheelbarger, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense. She warned that China used its economic power to establish a military presence in poor countries (what the present U.S. Administration calls a ‘debt-trap diplomacy’) [Lucht].

The broader foreign policy agenda is also involved. The United States denies the concept of China as a ‘near-Arctic state’, formalized in 2018 in China’s Arctic Policy. From this point, involving Greenland in the Polar Silk Road initiative is seen as a threat of China getting political influence in the Arctic.

Rare earth elements (REE), indispensable for modern electric and electronic devices, represent a third critical issue. China controls up to 98% of the global supply of some REEs [The Geopolitics of Rare Earth Elements]. The United States, therein its defense industry, imports over 70% of the REEs from China and is well aware of this vulnerability. It won a case in the WTO in 2014 and made China lift the REE export quotas. However, in late May 2019, days after President Xi Jinping visited JL MAG Rare-Earth Co in Ganzhou, a spokesperson from the National Development and Reform Commission indicated that PRC could ‘weaponize’ the rare earths in case of an escalation of the trade war with the U.S. [China indicates it may use rare earths as weapon…].

Greenland could potentially help breach this Chinese near-monopoly. REE have been discovered many places over the island rim. The most promising area, the Gardar Province in the south, may alone contain about a quarter of the world resources [Northam].

The U.S. vs Chinese approaches

The U.S. Administration has launched several broadly publicized initiatives on Greenland since mid-2019. These included signing two MOUs with Greenlandic ministries, a request to reestablish a Consulate in Nuuk and, above all, President Donald Trump’s sensational offer in August 2019 to buy the island from Denmark in what he presented as ‘a real estate deal’. Mette Fredriksen, the Danish Prime Minister, rejected the proposal as ‘absurd’ and stressed: ‘Greenland is not Danish. Greenland is Greenlandic’. Trump in turn called her ‘nasty’ and cancelled his planned visit to Copenhagen, but later on both parties tried to downplay the incident.

In April 2020, the U.S. Administration also announced a 12.1 million USD economic aid package for projects in Greenland within mining sector, tourism and education. The local Government, Naalakkersuisut, welcomed the offer as a sign of an increased bilateral cooperation, while it caused an outrage among many politicians in Copenhagen.

These, rather extravagant, steps represent nothing new really – President H.Truman offered to purchase Greenland as far back as in 1946. The U.S. decision-makers have since World War II viewed the island within the framework of the Monroe Doctrine, which, although voided formally 2013, still influences the American thinking [Berry]. But now this traditional approach is reinforced by the growing U.S. interest for the Arctic and its global clash with China.

Judging by its recent moves, the U.S. Administration seems to doubt Denmark’s capability of steering Greenland and would rather establish a more direct American control, even in a confrontational mode. This is very asymmetric to China’s soft approach. In the past couple of years, the Chinese have not been active in political contacts with Greenland, while sending dozens of employees to its fish processing units, arranging cultural exchanges and preparing large extractive projects. These include Kvanefjeld REE mine, the above mentioned Isua and Citronen fjord zink and lead mine in the north.

Kvanefjeld is among the biggest deposits in Gardar Province with resources worth net 1.4bn USD. Australia-based Greenland Minerals Ltd. holds the license, working in close partnership with its largest shareholder, Shenghe Resources Holding Co., Ltd. from Chengdu in Sichuan Province. The Kvanefjeld mine is poised to become its third major rare earth mine outside China [Hu Zesong].

While Americans have concerns about Chinese investments in Greenland, they do not seem ready to overbid China. For example, their activities in the Gardar Province are so far limited to a joint aerial survey in summer 2019 [Airborne hyperspectral survey…]. Instead, the U.S. prefer public policy moves and pressing on Denmark as its NATO ally.

This was not unexpected. We predicted in this journal in 2013 that at some point the U.S. would finally try to halt the growth of the Chinese presence in Arctic Scandinavia, relying on non-economic arguments. The focus on security policy and Atlantic solidarity would eventually pose the Nordic countries with complicated dilemmas [Krivorotov].

Denmark and Greenland at crossroads

Until recently, the Danes had been positive to Chinese activities in the Arctic, including investments in Greenland [Fuglede et al.]. Denmark was a strong supporter of China getting a permanent observer status in the Arctic Council in 2013.

However, as the region is getting involved in the great power rivalry, Denmark looks increasingly concerned about the fate of Greenland and the role of China [Mingming Shi and Lanteigne]. In November 2019, for the first time ever, the Danish Defence Intelligence Service (DDIS) started its annual open Risk Assessment with the Arctic, focusing on Russia and China. DDIS noted among other that in Denmark and Greenland ‘China is using increased cooperation on research and trade as entry points for influence’, stressing the close relations between the Chinese companies and the government [Danish Defence Intelligence Service, 2019; see also [Yang Jiang].

Over the past few years the Danish Government has sought to strike a delicate balance between maintaining the vitally important good relations with the U.S., retaining control over Greenland, and promoting investments there while limiting Chinese involvement.

The three airports project is a characteristic case. Besides warning Copenhagen against the Chinese, the U.S. Department of Defense indicated that it might itself invest in dual use infrastructure in Greenland. Denmark opted finally to avoid any foreign involvement by providing 450 million DKK (70 million USD) of public money [Øfjord Blaxekær, Lanteigne & Mingming Shi]. Danish politicians and observers think, however, that in the longer run an increased U.S. military presence in Greenland is inevitable.

Mette Fredriksen, the present Danish Prime Minister, cares visibly more about Greenland than her predecessors, both in terms of paying visits, rendering practical assistance and giving the island a formal say in Arctic foreign policy. When Danish Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod paid his first visit to Washington, DC in November 2019, he was accompanied by his Greenlandic colleague, Ane Lone Bagger, contrary to the previous practice [McGwin].

At the same time, as Danish journalist Martin Breum notes, a way of thinking has recently evolved in Copenhagen that the U.S. offer to buy Greenland will likely curtail Greenlandic secessionism. The island leaders should now realize that a ‘Greenland without ties to Denmark would rather… find that the U.S. will never accept other than total military control over all of Greenland’s territory’ and the island would end up living like ‘the U.S. Virgin Islands, which Denmark sold to the U.S. in 1916 and whose inhabitants, many of whom live below the poverty line, still have no voting rights in the U.S.’ [Breum].

Some Greenlanders, like the former Premier Aqqaluk Lynge, fear also that large-scale (Chinese) mining may destroy the traditional Inuit culture [Dyer], but the current government does not share these fears. Its immediate reaction to D.Trump’s offer was ‘We're open for business, not for sale’. Later on, Greenlandic executives at the Arctic Circle Assembly (Reykjavik, October 2019) and Kim Kielsen in an interview with M.Breum made it clear that they still pursue a complete independence. They foresee close ties with Denmark and a continued defense cooperation with the U.S. and NATO, while welcoming investments from all nations. In March 2020, Naalakkersuisut suggested to open a Greenlandic representation (quasi-embassy) in China, to complement those already established in Brussels, Washington and Reykjavik [Schultz-Nielsen].

Future prospects and Russian reactions

The current situation shows clearly that any Chinese Arctic activity, regardless of its nature, raises concerns and doubts in the U.S. and Denmark in both political, economic and security context. China is likely to face more troubles in Greenland and in the Norden at large in the years to come.

To the contrary, Russia is a major concern, but entirely in military terms. This is largely because Russian efforts concentrate in its own Arctic sector, where the U.S. acknowledge its legitimate interests [U.S. Department of State, 2020].

This may be the reason why the Russian media show limited interest to the situation on and around Greenland. Donald Trump’s bid for purchase was the only exception, viewed by most Russian analysts as just another move in the American Arctic and foreign policy, or global U.S.-China confrontation [Plevako].

The conservative Tsargrad TV predicted that the U.S. would continue pressing on Denmark and influence the Greenlandic public opinion to acquire the island one way or another [Kak 102 goda nazad…]. The proposed U.S. package for Greenland may somehow support this view indirectly, as the money will be channeled to various U.S. agencies and consultants, thus providing them with hands-on knowledge of Greenland and with soft power opportunities. ([1] It is noteworthy that the package amounts 12.1million USD, or some 210 USD per capita of Greenlanders, nearly twice as much as the U.S. had spent in Ukraine prior to 2014 (5bn USD per 45 million of population, about 110 USD per capita) [US Admits…].)

In our opinion, the development deserves a much closer attention in Russia, as this involves not merely a huge Arctic territory (which has among other put continental shelf claims overlapping with Russia’s), but also the two global powers. In the mid-term, one could foresee three scenarios:

1. Greenland remains politically united with Denmark, but enjoys a growing autonomy. U.S. military presence is enhanced under tripartite agreements. Denmark, vary of both American and Chinese interest to the island, increases public spending there, while Greenland continues its quest for financial self-reliance.

2. The United States, although does not ‘purchase’ Greenland, still leverages its military presence and financial aid programs to have the island formally and informally associated with the U.S. closer than with Denmark. The U.S. increases investments in military installations and potentially in REE production. It may also join the UNCLOS to support Greenlandic claims for the North Pole and the surrounding shelf. Contacts with China and Russia are limited to a minimum.

3. Greenland obtains a full-fledged statehood, pursues non-alignment and strives to get foreign investments on competitive terms in order to boost the economic development and the people’s well-being.

Under scenarios 1 and 2, Greenland turns into ‘a second Alaska’ for the U.S. protecting the Lower 48 from the north-east, with a resulting further militarization of the island and of the whole Central Arctic. Under scenarios 1 and especially 3, China will have opportunities for developing its bilateral political and business relations with Greenland, despite U.S. counteractions.

The next few years may be very important. Given the strategic importance of the Arctic for China and the limited number of Arctic territories where it may get a foothold, the competition for Greenland is likely to increase.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is an important game changer. It impacts China’s reputation as both the country where the virus originated, but also the one which was the first to cope with it, while the U.S. population and economy are hit hard. This may affect the global economic development, as well as domestic and foreign policies of all the nations concerned. And, though Russia has no immediate interests in Greenland, it should watch the development closely, as it is sure to impact the situation in and around Arctic in any case.

REFERENCES

Airborne hyperspectral survey and mineral mapping in South Greenland, Naalakkersuisut [Greenland Government]. 19 December, 2019. URL: undefined (accessed: 7 May, 2020).

Berry, Dawn Alexandrea (2016). The Monroe Doctrine and the Governance of Greenland’s Security. Governing the North American Arctic. Sovereignty, Security, and Institutions (Berry, D.A., Bowles, N. and Jones, H. (eds.). P. 103-121.

Breum, Martin (2020). Greenland’s premier doesn’t foresee a US takeover and remains committed to the quest for independence, Arctic Today, 20 January. URL: undefined (accessed: 6 May, 2020).

China indicates it may use rare earths as weapon in trade war (2019), Global Times, 28 May. URL: undefined (accessed: 6 May, 2020).

Danish Defence Intelligence Service (2019). Intelligence Risk Assessment 2019. Copenhagen: DDIS. 59 p.

Dyer, Gwynne (2019). Greenland's big gamble on Chinese mining, Bangkok Post, 21 August.

Fuglede Mads, Kidmose Johannes, Lanteigne Marc and Schaub Gary Jr. (2014). Kina, Grønland, Danmark – konsekvenser og muligheder i kinesisk Arktispolitik [China, Greenland, Denmark – consequences and opportunities in Chinese Arctic policy], København (Copenhagen): Center for militære studier, V+46 p. (In Danish).

Hu Zesong (2019). Investment in Greenlandic Mining, Site of Greenland Mining Co., Ltd. URL: undefined (accessed: 5 April, 2020).

Johnson Simon and Wroughton Lesley (2019). Pompeo: Russia is ‘aggressive’ in Arctic, China’s work there also needs watching, Reuters, 6 May. URL: undefined (accessed: 8 January, 2020).

Kak 102 goda nazad. Stalo yasno, kak SShA budut otbirat’ Grenlandiju u Danii [Like 102 years ago. It is clear now how z U.S. will deprive Denmark of Greenland], Tsargrad TV, 21 August, 2009. URL: undefined (accessed: 10 May, 2020).

Käpylä Juha and Mikkola Harri (2019). Contemporary Arctic Meets World Politics: Rethinking Arctic Exceptionalism in the Age of Uncertainty, The GlobalArctic Handbook, P. 153-169.

Krivorotov, Andrey (2013). Arktisheskaya aktivizatsiya Kitaya: vzglyad iz Skandinavii [Arctic Activation of China: a View from Scandinavia], Kitaj v mirovoj i regionalnoj politike. Istoriya i sovremennost [China in World and Regional Politics. History and modernity], Moscow: IDV RAN (IFES FAS), Iss. ХVIII: 158-192. (In Russian).

Kuo, Mercy A. (2019). Greenland in US-Denmark-China Relations. Insights from Jonas Parello-Plesner, The Diplomat, 2 October. URL: undefined (accessed: 08 January, 2020).

Lucht, Hans (2018). Strictly business? Chinese investments in Greenland raise US concerns, DIIS Policy Brief, November. 4 p.

McGwin Kevin (2019). Greenland is high on the agenda as Denmark’s new foreign minister makes his first DC visit, Arctic Today, 13 November. URL: undefined (accessed: 22 April, 2020).

Mingming Shi and Lanteigne Marc (2019). China’s Central Role in Denmark’s Arctic Security Policies, The Diplomat, 8 December. URL: undefined (accessed: 22 April, 2020).

Northam, Jackie (2019). Greenland Is Not For Sale. But It Has Rare Earth Minerals America Wants, NPR Radio, 24 November. URL: undefined (accessed: 6 May, 2020).

Øfjord Blaxekær Lau, Lanteigne Marc & Mingming Shi (2018). The Polar Silk Road & the West Nordic Region, Arctic Yearbook (Heininen, L., & H. Exner-Pirot (eds.), P. 437-455.

Plevako, Natalia (2019). Grenlandiya v planakh Trampa: vozrozhdenie “diplomatii dollara”? [Greenland in Trump’s Plans: Revival of ‘Dollar Diplomacy’?], Nauchno-analiticheskiy vestnik IE RAN [Scientific and analytical bulletin of the Institute of Europe, IFES RAS], No. 5: 60-65. (In Russian).

Schultz-Nielsen Jørgen (2020). Ny repræsentation på vej i Kina [New rep office in the making in China], Sermitsiaq, 23 marts. URL: undefined (accessed: 04 April, 2020). (In Danish).

The Geopolitics of Rare Earth Elements, Stratfor, 8 April, 2019. URL: undefined (accessed: 4 December, 2019).

The GIUK Gap’s strategic significance, Strategic Comments, 2019, Vol. 25, Comment 19, 3 p.

U.S. admits it spent 5 billion to overthrow Ukraine, Infowars.com, January 29, 2019. URL: undefined (accessed: 14 May, 2020).

U.S. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Arctic Strategy, Report to Congress, June, 2019. 18 p.

U.S. Department of State. Briefing on the Administration's Arctic Strategy, 23 April, 2020. URL: undefined (accessed: 14 May, 2020).

Yang Jiang (2018). China in Greenland: companies, governments, and hidden intentions?, DIIS Policy Brief, October. 4 p.

Source: China in World and Regional Politics: History and Modernity (annual). Vol. XXV. E.I.Safronova (ed.). Moscow, 2020.